6 Major Flaws that make the Impact vs. Effort Matrix Obsolete

Almost certainly, you’ve come across a 2x2 matrix in your prioritization work. These are ubiquitous visual aids for mapping priorities and deciding on what you should be doing or delegating. The Impact vs. Effort chart is a popular visualization in business and product prioritization. Variants of it can be applied to pretty much any pair of cost and benefit components. The technique supposedly lets you visualize in a simple 2x2 matrix rough categories for what you should do first and what you should avoid.

Unfortunately, these 2x2 matrices are misleading at best, and downright harmful at worst. Product Management training materials from the most reputable sites (ProductPlan, MindTheProduct, Monday.com, SixSigmaDaily to name a few) teach the 2x2 matrix, apparently blissfully unaware that it’s dangerously incorrect. In this article, I’ll show you how relying on the 2x2 matrix is making your decisions worse and losing your team’s precious time and value. And, I’ll also show you how to modify the classic 2x2 to avoid the biggest flaws and make the best possible decisions when comparing ideas on a value axis vs an effort axis.

For this article, we’ll focus on the Impact vs. Effort matrix so that I can use the conceit of referring to it instead as Effort vs. Impact, or EvI, which happens to look like the word “Evil”. “IvE” doesn’t have the same ring.

“Relying on the 2x2 matrix is making your decisions worse and losing your team’s precious time and value.”

A brief reintroduction to the EvI (2x2) Matrix

Guides to this are ubiquitous on the ol’ interwebs, so I’ll be brief.

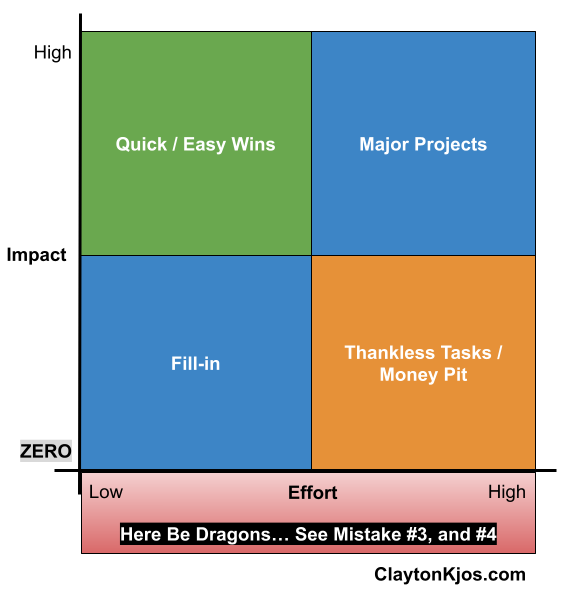

The usual EvI matrix is broken down into four equal parts.

“Big Bets” or “Major Projects” for the high impact, high effort quadrant.

“Quick/ Easy Wins” for the high impact, low effort quadrant.

“Thankless Tasks” or “Money Pit” for the high effort, low impact quadrant.

“Fill Ins” for the low effort, low impact quadrant.

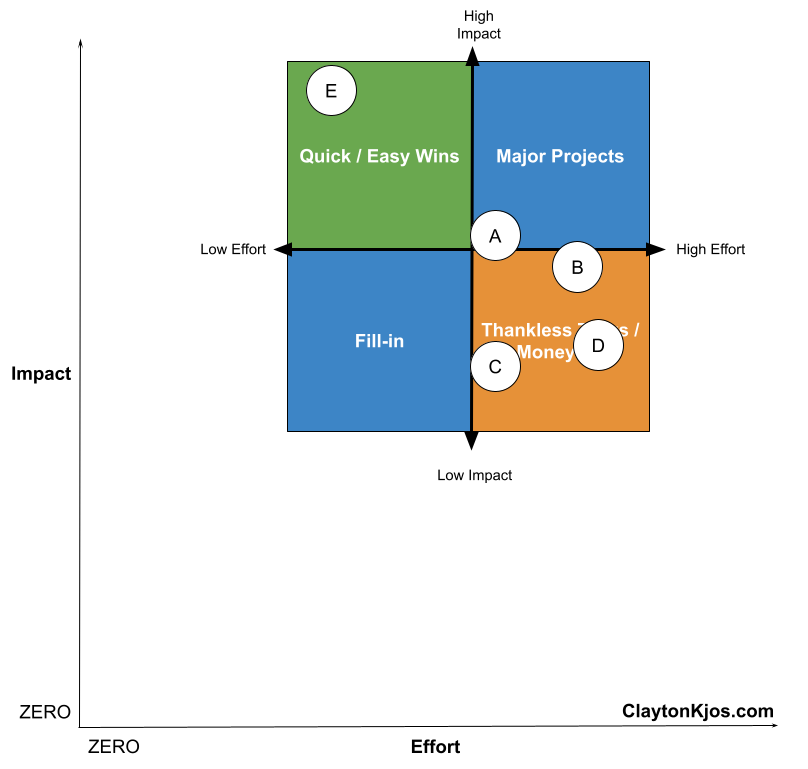

Diagrams #1 and #2 below show two variants for how the EvI Matrix is typically constructed.

Diagram #1: Variant of the Impact Effort Matrix with arrows from the center.

Diagram #2: Variant of the Impact Effort Matrix with the scale on the left and bottom.

To use the chart, you typically score your ideas by effort and impact and then place it in its respective spot within the four quadrants. You’ll focus first on quick wins, followed by big bets, then fill-ins, and finally, or never, you might take on thankless or money pit tasks as show in Diagram #3.

Diagram #3: Order the quadrants are typically prioritized using the matrix alone. This is not necessarily the order tasks are completed in. This is the order productplan describes.

Sounds pretty simple. It’s certainly pretty easy to use. And yet, it’s completely broken.

Flaw #1: Quadrants are misleading you on relative Priority

When we compare with impact and effort, we perform a calculation. We take the impact and divide it by the effort. This results in a simple score that we compare with other tasks; higher is better, lower is worse. This is what we do in RICE, WSJF, ICE, CD3, and many other priority scoring systems.

When we do this simple division, what we’re really doing is calculating the slope of a line. It’s the old pre-algebra standard y = m*x + b where b=0, y = impact, x = effort. We solved for M by dividing both sides by x and viola y/x = m. Okay, that’s all the math we need from here on, I swear.

A funny thing just occurred. We calculated a priority score that doesn’t map to our matrix at all! All items on our chart where the priority score is the same value land on the same line, but not necessarily the same quadrant!

By drawing a few sample lines, we can easily see there are lines that transit not just one quadrant, not just two, but up to three quadrants. This means three different ideas with the same priority score could be treated completely differently because of the quadrant, while other lower priority score items might be favorably compared to the first three, again, because of the quadrant.

Diagram #4: Example Priority Lines crossing 3 quadrants.

In Diagram #4, tasks that fall on Line A all share the same slope, and thus the same priority score, yet they may lie within Easy Wins, Major Projects, or Fill-in. Tasks that fall on Line B also share the same priority score, yet they may lie within Major Projects, Fill-in, or Thankless Tasks.

Everything in Line A is higher priority than everything in Line B, regardless of quadrant.

Diagram #5: Example of 3 equivalent priority tasks, each in a different quadrant.

In Diagram #5, three tasks each share the same priority score but are each in a different quadrant. Based on the standard behavior for the EvI Matrix, task B would be tackled immediately, task A would be broken down, and task C would perhaps not get done at all. However, they are all the same effective priority!

Diagram #6: Chart showing very closely prioritized tasks, but in different quadrants.

We can also see in Diagram #6, that items very close to the center of the chart might have 4 completely different quadrant assignments. As a result, these tasks will be treated completely differently even though the difference in priority score is marginal at best (and identical for items A and C).

We’re only one flaw in and it is immediately obvious that the quadrants utilized in the EvI Matrix are, well… evil.

Flaw #2: Effort and Impact are Ambiguously Dependent or Independent.

Okay, so that probably sounds ambiguous too… bear with me. The thing is, the word “impact” is ambiguous. We can apply it to business metrics, product KPIs, or pretty much anything that suits our needs. Sometimes, those metrics account for effort (ROI, Cost of Delay, Profit, Etc); in that case, effort and impact are dependent. Changing the effort value for a task may also change the impact though the reverse is rarely true.

On the other hand, we sometimes use value metrics that are completely independent, like revenue. Our chart, and how we analyze it changes significantly depending on what we choose for impact. And yet, that’s completely lost; so let’s explore briefly how different the interpretation really is.

Diagram #7: Independent Impact Chart with overlays to highlight where our zero line is.

When effort and impact are independent variables (or you happen to use them that way), then there would be some non zero, positive sloped line that represents the threshold at which there is zero net benefit as in Diagram #7. Below that line you start moving into unprofitable, net negative returns (see Flaw #3).

Diagram #8: Dependent Impact Chart that looks like the charts we’ve been using.

On the other hand, when the variables are dependent, our lowest (or zero) impact line represents the balance between cost and benefit. In Diagram #8, we’ve noted that the bottom of the impact axis is explicitly zero. In many scoring systems, the impact and effort estimates might use a scoring system with minimum and maximum values that are all positive. When that isn’t the case, see Flaw #4.

In truth, something like Diagram #1 or #2 are the most common representations of the matrix. It Neither acknowledges nor states whether the variables are independent or not, but dependency is implied. This ambiguity can render the chart unrelatable from one team to the next.

Does using a dependent chart (Diagram #8) make things easier or harder?

The standard charting provides us more room to read the chart. On the other hand, it also means that by changing the effort required for a task, the impact may change! And when that happens, funny things occur to the quadrants the tasks live in. Doh! That can be hard to track with just a simple EvI Matrix! There are some variants, such as CD3 which eliminate this by choosing alternative positive and negative metrics. CD3 is highly preferred over simple EvI matrices, but that’s another topic.

Flaw #3: Big Impacts can have net negative ROIs!

There’s a space in our EvI Matrix where our ideas lose money or hurt our KPIs. The standard EvI Matrix ignores this completely. Egads! Many versions of the chart simply show an arrow to “Low Impact” and don’t represent zero at all. For those, there may be a fairly large gap between what you might consider a money pit task and an actual loss generator (see Flaw #4).

Diagrams #7 and #8 (above) highlight where the actual money pit area is in your charts. The area labeled “Here Be Dragons” is your actual money pit. In Diagram #7, you can see that you might have very high impact items in the upper right corner of the diagram that will lose you money.

What kinds of things end up below the break even line?

Ideas that don’t pay for themselves are plentiful when impact is measured in revenue. We also have a lot of ideas coming into our queues that have a real likelihood of providing a negative gross effect on our impact KPI, financial or otherwise.

Clearly, we need to acknowledge that your ideas may have a negative impact and ensure that’s represented. No, you don’t get to simply dismiss or reject them; as we found out earlier, if we can change the effort associated with an idea, it may end up very beneficial.

Flaw #4: The Matrix simply floats around, wandering across your idea landscape at will.

In many representations of the 2x2 we don’t have a zero line for effort or impact. Rather, we have “more” and “less” on the ends of each line. ProductPlan and MindTheProduct use these untethered representations (Diagram #1). This matrix is simply floating somewhere, ready to be resized - and thus the simple act of adding one more idea might completely change the evaluations of our other ideas. Adding a single new idea at the extremes causes all the previous ideas to slide in the opposite direction, collecting at the other extreme. Quick Wins become Money Pits. Money Pits become Quick Wins. Fill-ins become Major Projects. And, Major Projects become Fill-Ins. Ridiculous.

Diagram #9: The original EvI Matrix simply floats somewhere in the space of impacts and efforts greater than zero.

The Matrix simply floats out there, untethered to concrete values.

Diagram #10: Adding a new high value, low effort idea changes the relative evaluations of our old ideas.

The old Quick Win suddenly isn’t. The Major Project and Fill-in Ideas are now a money pit despite no change to their actual priority score.

Diagram #11: Adding a new lower value, low effort item makes more tasks major projects

Now we only have Fill-In Tasks and Major Projects…

Diagram #12: Adding a low value, high effort item makes more tasks quick wins.

All our old ideas, even those in the Money Pit, are suddenly Quick Wins.

Play with Gravity and Manipulate Product Space-time

MindTheProduct (for one) suggests you balance your chart “so there are roughly the same amount of cards in each quadrant.” Basically, they put handles on the midpoint in space-time and let you drag it around until you get a chart that looks better.

Let’s break this recommendation down to fully understand it. First… objectively score and place the items on the chart. Second… because it might look bad, arbitrarily move everything around. The reasoning for this is because relative priority is what matters and there’s so much error in trying to be precise. So, you must add some more error to balance it out. I’m not a fan. The sad fact about this article on MindTheProduct is that it’s focused on reducing poor prioritization - and yet its solution is… poor prioritization. Ugh!

I want to be extremely clear. MindTheProduct is not alone in this recommendation. They almost certainly didn’t originate it. They have many excellent resources. This isn’t one of them. They simply have the dubious honor of being well ranked for SEO on the topic.

Relativity in Prioritization

The floating nature of the charts and the flexibility with which tasks may be recategorized might be labeled a feature for relative prioritization. Relative priority is certainly sufficient when making a decision between two otherwise good options. However, it doesn’t answer the question of whether you should do either, neither, or both of the options. It doesn’t give you any information on how much more valuable one option is likely to be vs another. Given what we already know about the quadrants (Flaw #1), when applied utilizing the EvI Matrix, the ‘relative priorities’ are wrong.

Flaw #5: The Matrices do not work across Teams.

When the EvI Matrix isn’t floating, it is usually made up of a set or range of values. Sometimes this range is explicit, such as 0-10, and sometimes it’s simply implied by the visualization itself. Regardless, the visual space is bounded by how you draw it. So there’s always an upper limit placed on effort and impact after which you hit that boundary.

Two teams generating equivalent value might have charts where the boundaries are completely different based on how they broke down those ideas. A direct comparison can lead you to make terrible decisions about what to do between these teams. Let’s look at an example.

Diagram #13: Team A’s Ideas - all with relatively large scales.

Team A tends to generate a few big ideas and will have relatively larger boundary ranges.

Diagram #14: Team B’s Ideas - all with relatively small scales.

Team B generates lots of small ideas and will have relatively smaller boundary ranges.

Just glancing at these two together gives you the impression they are equivalently set up and can be easily compared in one chart. This isn’t true. Let’s try it and see what happens…

Diagram #15: Team A’s Ideas and Team B’s Ideas on the same chart with Team B’s at 50% impact/effort scale. Team B’s Ideas in Yellow.

In Diagram #15, we’ve put the two charts on the same impact and effort scale. This resulted in all of Team B’s ideas being moved into the “fill in” category, even when it was in their team’s quick wins, or money pit areas before! Team B’s ideas simply wouldn’t get implemented. You might fall into the trap of choosing to focus on Team A, even if Team B’s aggregate ROI was higher. Our decision making became relative to how teams generate and scale ideas with a preference against teams who do more incremental work! Ugh! As if we still needed more reasons to abandon the quadrants!

This one goes to 11…

The truth is that effort and impact are unbounded. There should be no outer bound to your chart. There’s no 10 out of 10 effort that translates from team to team. And, there’s no 10 out of 10 effort that can’t be beaten by another bigger idea that comes along. The same is true for impact. There’s always something that can be better than 10 and worse than -10 (or whatever you were thinking to apply after realizing impact can be negative). So whether you use real values, scoring, fibonacci estimates, or binary estimates, remember that your scale for value shouldn’t have boundaries. Effort is similarly unbounded on the positive side - though it is bounded at zero effort.

Flaw #6: Biased towards BIG instead of Effective.

The EvI Matrix has a bias towards big effort over big ROI. We saw this with Team B in Flaw #5. The fill-in quadrant is often described as an area whose ideas you should probably not do - unless you don’t have anything else (see any of our references). Ironically, the big bets are often described as ideas you should break down into smaller units, which would make them “fill-ins” much of the time.... which we don’t do? Confusing!

The order of operations works out to: Do all quick wins, break down big bets until they are fill-in sized, then ignore them and simply don’t do the high effort low value stuff even if you could break it down to fill in size. The result is that three quarters of the EvI matrix are effectively ignored even when they are very high ROI options.

The 2x2 is supposed to be Lean

Both ProductPlan and MindTheProduct make the claim that the 2x2 Matrix is “Lean.” The assertion is that because it’s simple, you can focus on valuable work, eliminate waste, and be more lean. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. The 2x2 matrix may be simple but it’s blatantly incorrect. It leads you to choose low value work, to prioritize big, potentially wasteful projects over incremental improvements, and is generally arbitrary. In aggregate, the 2x2 is more prone to introducing waste than removing it.

Tear up your old Effort vs. Impact Matrix - it’s making you less effective!

We’ve covered 6 Flaws that make the classic 2x2 Impact vs. Effort Matrix evil. You’ve seen that it’s arbitrary and error prone. You’ve seen that it’s common to manipulate it for aesthetics instead of results. You’ve seen that it can be improperly bounded and often ignores swathes of ideas. The 2x2 is anything but lean. This simple method of visualizing and categorizing ideas and tasks is deeply flawed in confounding and confusing ways. It is time to throw it out.

All is now lost for Effort vs. Impact visualizations. In my companion article, “Replace your 2x2 Impact vs. Effort Matrix!” I show you how to run the same ideation process with a brand new way to understand your priority visually that avoids all the pitfalls and mistakes of the 2x2.

References

ProductPlan Post on 2x2 Matrix

ProductPlan. "2x2 Prioritization Matrix." ProductPlan, 2023, https://www.productplan.com/glossary/2x2-prioritization-matrix/.MindTheProduct Post on the 2x2 Matrix

Wicks, Andy. "Enter the Matrix - Lean Prioritisation." Mind the Product, 2017, https://www.mindtheproduct.com/enter-matrix-lean-prioritisation/.Monday.com post on Impact vs. Effort Matrix

All of us at monday.com. “How an impact effort matrix can help you prioritize tasks” Monday.com, 2022, https://monday.com/blog/project-management/impact-effort-matrix/Six Sigma Daily post on Impact vs. Effort Matrix

Six Sigma Daily. (2023, May 18). How to use the impact effort matrix. Retrieved from https://www.sixsigmadaily.com/how-to-use-the-impact-effort-matrix/